Bethlehem / PNN/

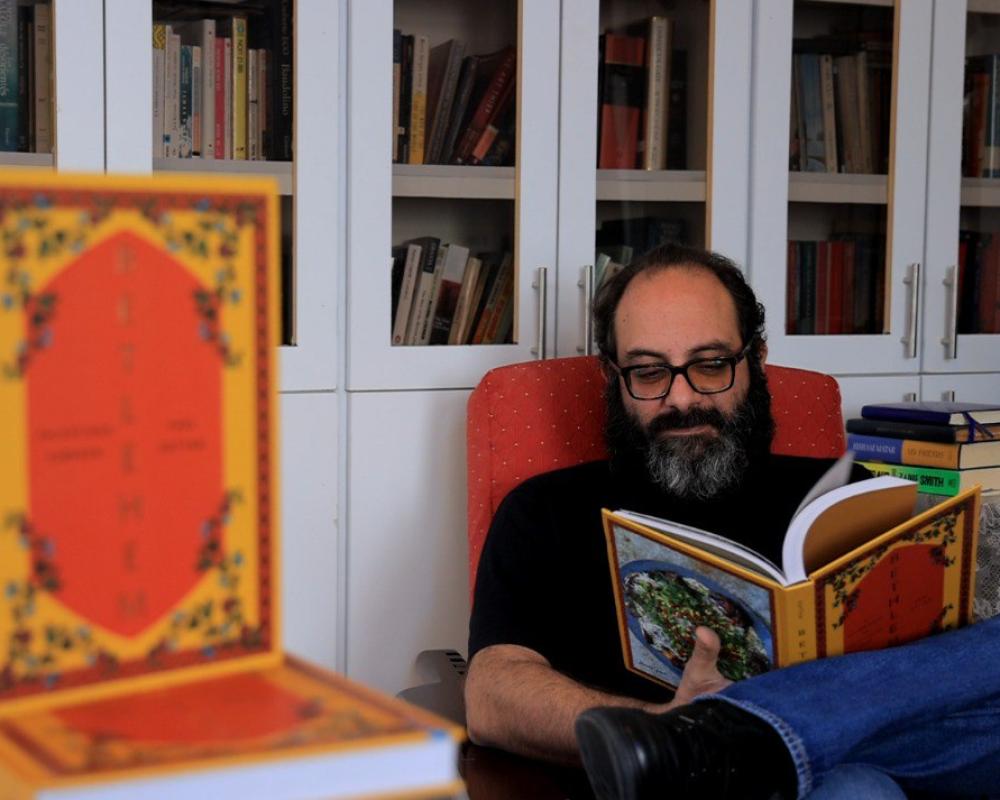

In the heart of Bethlehem, where the land breathes history and echoes with memories, Fadi Kattan was born—a Palestinian chef now celebrated on a global stage. Fadi is not just a chef; he is an ambassador of Palestinian cuisine, infusing each dish with the rich flavors and history of his homeland. From Bethlehem to London and Toronto, Fadi has carried "Palestine" on his plates, embedding his culinary creations with his identity and heritage.

Fadi's journey began in his grandmother's kitchen, where he learned the secrets of Palestinian cooking handed down through generations. His mother and grandmother were his primary mentors, teaching him the oral traditions of Palestinian cuisine. Each recipe he acquired from them carried a unique touch, a signature flavor that varied from household to household yet remained unmistakably Palestinian. To this day, he frequently calls his mother for advice or a recipe, strengthening the bond between his craft, his family, and his homeland.

After honing his skills in France, Fadi returned to Bethlehem to find a city transformed by conflict. The Second Intifada had shuttered many businesses, leading him to work in various fields before opening his own restaurant, "Fawda" (Chaos), in Bethlehem. This venture marked a fresh chapter, allowing him to showcase the authentic spirit of Palestinian cuisine. Fadi’s food does more than nourish—it brings people together and serves as a powerful expression of collective identity.

For Fadi, Palestinian cuisine transcends cooking; it is a statement of identity. "Our cuisine is our Palestinian identity," he explains, emphasizing that Palestinian food isn't merely for tasting—it’s part of a cultural struggle. When the occupation appropriates the flavors of olive oil or rewrites the story of knafeh, it isn’t just food being stolen; it’s the memory and heritage of an entire people. Palestinian food is a bridge connecting Palestinians to their land, a story passed down through generations rather than written in books.

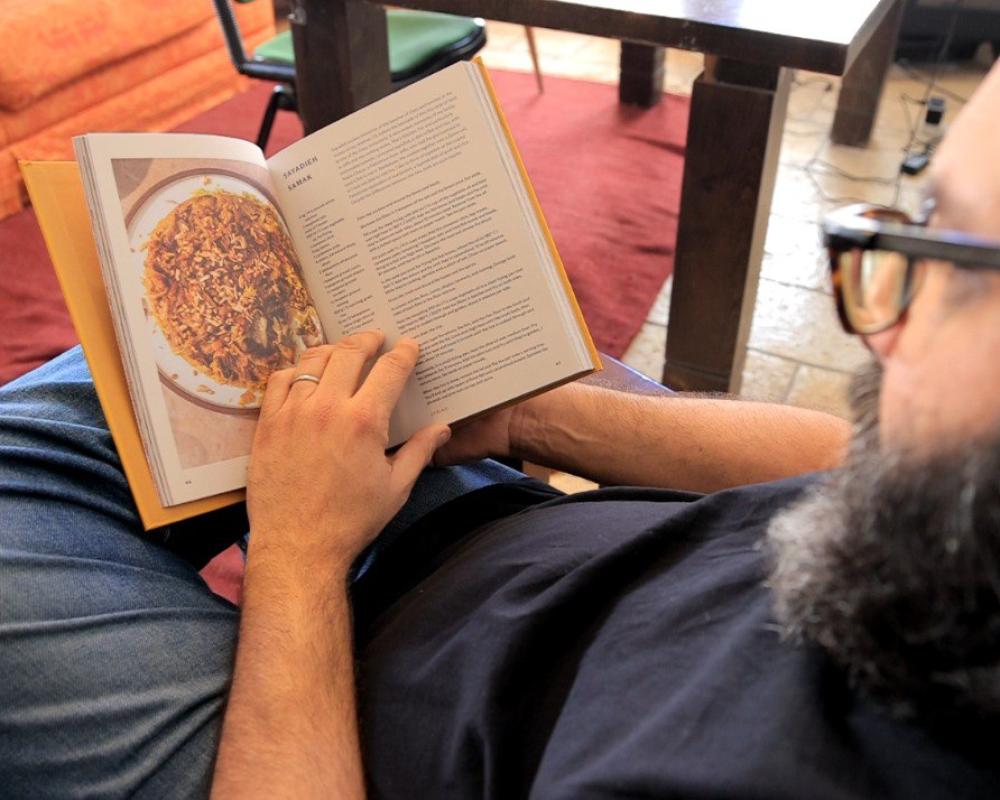

This deep understanding of his culinary heritage culminated in his book "Bethlehem", a labor of love written over three years. The book delves into the lives of Bethlehem's people and their traditional recipes, intertwining stories and flavors to preserve a cultural legacy. It has resonated worldwide, translated into several languages, and was named one of the "Top 20 Cookbooks" by The Los Angeles Times. While Fadi hadn’t expected such recognition, he always believed Palestinian cuisine was a powerful medium for sharing his people’s stories.

From his kitchen in Bethlehem’s Old City, Fadi weaves tales of families and individuals, such as his aunt Umm Nabil, who has sold herbs in the market for over 40 years, and the Natsha family, who have been butchers for three generations. His book reminds readers that Bethlehem is not merely a tourist destination or a religious site but a vibrant, living city steeped in history and culture—a mosaic of stories and traditions.

For Fadi Kattan, every dish tells a story, and every story is a testament to the resilience, identity, and enduring spirit of the Palestinian people. Through his food, he invites the world to experience Bethlehem—not just as a place, but as a living, breathing heritage.

Fadi Kattan, a celebrated Palestinian chef, doesn’t just serve recipes; he intertwines them with a rich and enduring Palestinian history. In his book, he recounts tales of Jaffa oranges, which he describes as a dream of flavor, and Palestinian knafeh, a dessert that is an integral part of the Palestinian identity, unmatched by any foreign imitation. Despite living abroad in London and Canada, Fadi remains steadfast in using authentic Palestinian ingredients. He brings sumac, za’atar, and Palestinian wine to blend with local flavors wherever he goes. For Fadi, food is not merely sustenance but a narrative of the Palestinian land, one that transcends borders and walls.

Over time, Fadi’s book, Bethlehem, has evolved into more than a cookbook; it has become a cultural and historical document, weaving stories of Palestinians across the diaspora. He shares the story of a man from Australia who reached out to him, seeking a Palestinian recipe his grandmother had preserved from the village of Jifna—a man who cannot visit Palestine due to barriers and the apartheid wall. This exemplifies how food bridges distance and keeps memories alive.

Amid the outbreak of war on October 7, 2023, as Palestine endured massacres in Gaza and the West Bank, Fadi faced the dilemma of promoting his book during a time of tragedy. Yet, he remained resolute in his belief that food is a powerful medium for conveying his people’s stories to the world.

When discussing Palestinian wine, Fadi proudly highlights the ancient roots of Palestinian viticulture. He recounts how Palestinians cultivated grapes and produced wine since antiquity, exporting their wines from Gaza’s port to the world. “We are the oldest people to plant vines and make wine. This is our story, and this memory will not be stolen from us,” he declares with pride.

Ultimately, Fadi Kattan continues to cook not just for the love of food but to preserve the memory of his people. Through his dishes, he sends a powerful message: Palestinian cuisine is more than just food; it is a symbol of identity and resilience, a testament to a land and a people who endure against all odds.

Palestinian cuisine is a tapestry of history, culture, and tradition, interwoven with the flavors of the Levant and shaped by centuries of agricultural heritage. More than just a collection of recipes, it reflects the resilience, resourcefulness, and communal spirit of its people.

The roots of Palestinian cuisine date back thousands of years, drawing from ancient Canaanite agriculture and incorporating influences from Arab, Ottoman, and Mediterranean traditions. Jericho, the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city, is testament to the deep agricultural heritage of Palestine. Staples such as olives, figs, and grapes—cultivated for millennia—remain vital ingredients in the Palestinian kitchen.

Palestinian cooking is deeply tied to the land, making use of fresh, seasonal ingredients. Olive oil, often referred to as "liquid gold," is central to almost every dish, symbolizing the resilience of Palestinian farmers. Other iconic flavors include za’atar (wild thyme), sumac, tahini, and freekeh (roasted green wheat). These ingredients are not just food items—they are cultural artifacts, passed down through generations.

In the face of displacement and occupation, Palestinian cuisine has become a form of resistance and identity. Cooking traditional dishes preserves cultural heritage and strengthens ties to the land. Ingredients like za’atar, olives, and figs are not just foodstuffs; they are symbols of connection to the soil.

Even in exile or diaspora, Palestinians recreate their culinary traditions as a way of staying connected to their roots. Stories of mothers and grandmothers teaching recipes to younger generations are common, ensuring that the flavors of Palestine endure.

In recent years, chefs like Fadi Kattan have brought Palestinian cuisine to an international audience, showing the world its complexity, depth, and beauty. Palestinian restaurants and cookbooks are gaining recognition, offering a taste of a culture too often overlooked.

This story was produced as part of the Qarib project implemented by CFI, the French media development agency, in partnership with and funded by AFD, the French Development Agency.